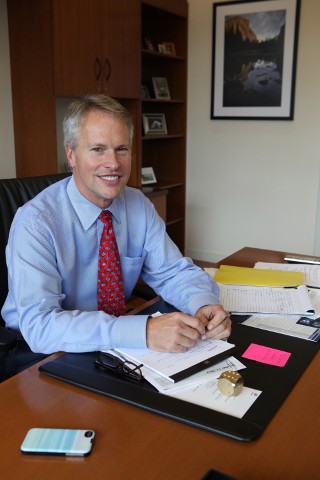

By Gary Pruitt

President and CEO

The Associated Press

It’s getting harder and more expensive to use public records to hold government officials accountable. Authorities are undermining the laws that are supposed to guarantee citizens’ right to information, turning the right to know into just plain “no.”

Associated Press journalists filed hundreds of requests for government files last year, simply trying to use the rights granted under state open records laws and the U.S. Freedom of Information Act. What we discovered reaffirmed what we have seen all too frequently in recent years: the systems created to give citizens information about their government are badly broken and getting worse all the time.

We’re talking about this issue now because of Sunshine Week, created a decade ago to showcase the laws that give Americans the right to know what their government is up to. These days, Sunshine Week is a time to put a spotlight on government efforts to strangle those rights.

The problem stretches from town halls through statehouses to the White House, where the Obama administration took office promising to act promptly when people asked for information and never to withhold files just because they might be embarrassing.

Act promptly? Hardly.

Shortly after Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 went missing over the South China Sea, we asked the Pentagon’s top satellite imagery unit, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, what the U.S. was doing to help the search.

Agencies are supposed to give at least a preliminary response to such questions within 20 days. A full year later, after the largest and most expensive search in aviation history, the agency is telling us only it has too many FOIA requests to meet its deadlines.

A few months ago, the Treasury Department sent us 237 pages in its latest response to our requests regarding Iran trade sanctions. Nearly all 237 pages were completely blacked out, on the basis that they contained businesses’ trade secrets.

When was our request? Nine years ago.

It takes the State Department about 18 months to answer — or refuse to answer — anything other than a simple request. This week we filed a lawsuit against the department for failing to turn over files covering Hillary Rodham Clinton’s tenure as secretary of state, including one request we made five full years ago.

As the president said, the United States should not withhold or censor government files merely because they might be embarrassing.

But it happens anyway.

In government emails that AP obtained in reporting about who pays for Michelle Obama’s expensive dresses, the National Archives and Records Administration blacked out one sentence repeatedly, citing a part of the law intended to shield personal information such as Social Security numbers or home addresses.

The blacked-out sentence? The government slipped and let it through on one page of the redacted documents: “We live in constant fear of upsetting the WH (White House).”

To its credit, the U.S. government does not routinely overcharge for copies of public records, but price-gouging intended to discourage public records requests is a serious problem in many states.

Officials in Ferguson, Missouri, billed the AP $135 an hour for nearly a day’s work merely to retrieve emails from a handful of accounts about the fatal shooting of Michael Brown. That was roughly 10 times the cost of an entry-level Ferguson clerk’s salary.

Other organizations, including BuzzFeed, were told they would have to pay unspecified thousands of dollars for emails and memos about Ferguson’s traffic citation policies and changes to local elections.

Last year, the executive editor of the South Florida Gay News asked the Broward County Sheriff’s Office for copies of emails that contained a derogatory word for gays. The sheriff’s office said it would cost $399,000 and take four years. “They succeeded in stonewalling me,” said the editor, Jason Parsley.

In Mississippi, the state Education Department demanded more than $70 an hour to review records when a reporter asked for its reorganization plans.

Despite head-pounding frustrations in using them, the Freedom of Information Act and state open records laws are powerful reporting tools. But it’s important to remember that they don’t exist just for journalists.

They are there for everyone.

The right to know what public officials are doing, how they’re going about it, what money they are spending and why … that right belongs to all citizens.

Government works better when the people who put it in office and pay for it with their taxes have an unobstructed view of what it is doing.

And that is why it is vital that we all fight every attempt _ from federal foot-dragging to outrageous photocopying bills _ to hide the public’s information behind a big, padlocked door. We need to let the sun shine in.

___

Gary Pruitt, president and CEO of The Associated Press, is a former First Amendment lawyer.

This column is part of a package prepared by The Associated Press, the American Society of News Editors, McClatchy and Gannett to mark Sunshine Week, created to highlight the continuing fight for access to public information.