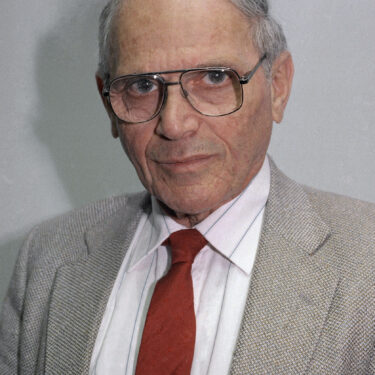

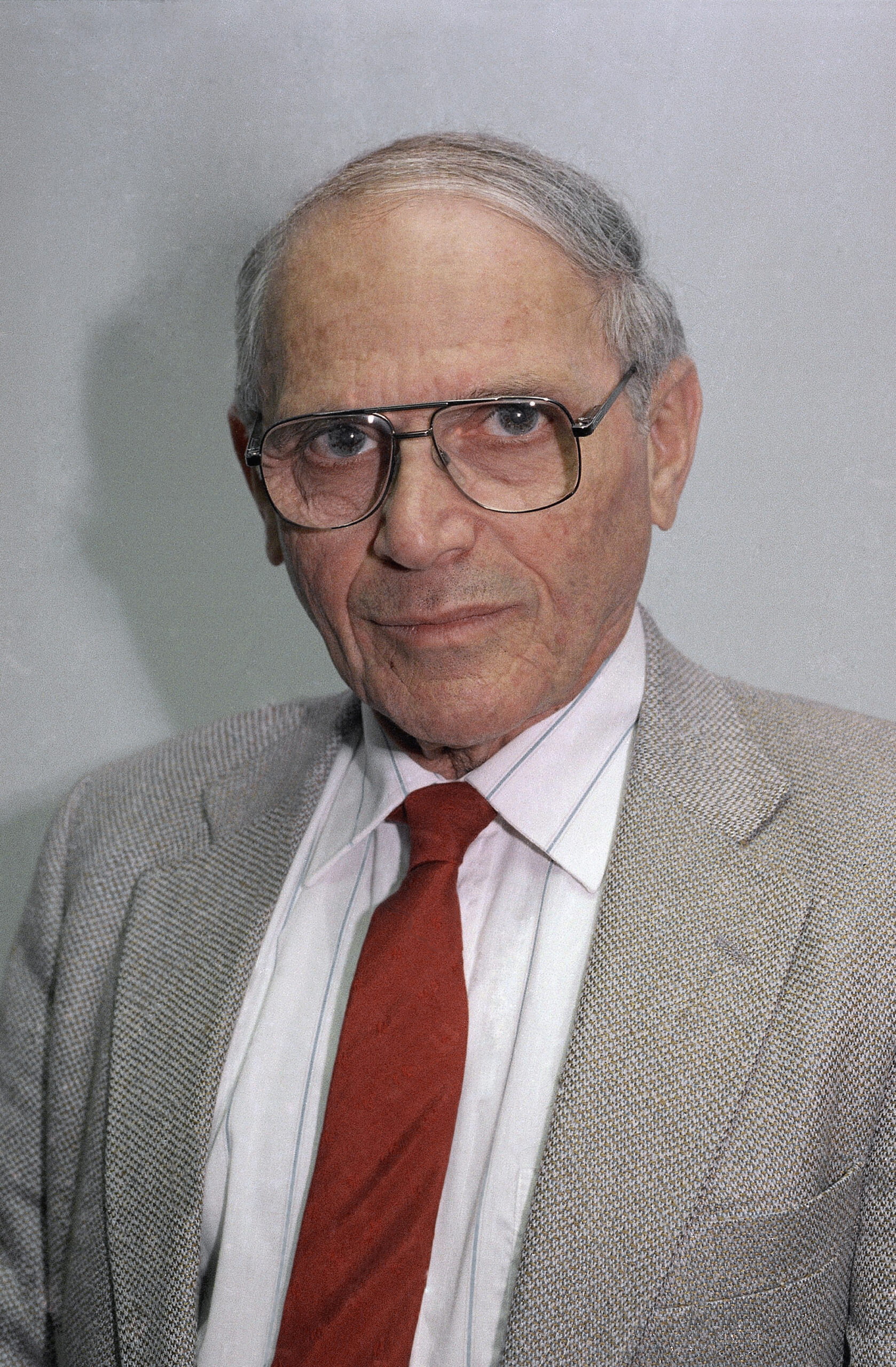

WASHINGTON (AP) — Harry F. Rosenthal, an Associated Press writer who covered America's golden age of space exploration, presidents back to Harry Truman and whatever caught his impish eye in the stuffy halls of power, has died. He was 86.

He died Thursday at home in Kansas City, Mo., his daughter, Lesli Mulligan, said.

From the start, Rosenthal was more than a top-tier wire service newsman, fast and accurate. He was a wordsmith. He sweated the details, then turned those details into irresistible prose. In the old days when newsrooms still reeked of cigarettes, he would smoke and pace and fret while pondering just how he wanted to tell a story.

“Writing bugs me,” he said, “but it’s the only way I like to make a living.”

Curiosity, Rosenthal believed, was the essence of good reporting.

“My own approach to an interview is the same one I had at 16 when I went to my first burlesque show,” he said. “I had an idea of what to expect but I wanted to see for myself.”

Rosenthal strolled with Truman in Independence, Mo., as the retired president reflected on his decision to drop the atomic bomb on Japan at the end of World War II. He covered Dwight Eisenhower back home in Kansas, Richard Nixon in his downfall and death, and presidents through to Bill Clinton before he retired from the AP in 1997.

He said then he wished he could write the human story of five more decades. He had a nose for the kind of story people wanted to read.

“We call them ‘Hey, Martha’ stories,” Rosenthal said. “Which is, the guy sitting at the breakfast table and saying, ‘Hey, Martha, did you see this?’ You want a story with impact.”

There were plenty of those in a career spanning a half century associated with the AP, first as a stringer, then for more than 40 years a staff member, then a columnist in his retirement.

He wrote about the My Lai massacre prosecution of Lt. William Calley, the trials of assassin Sirhan Sirhan and would-be assassin John Hinckley. He covered civil-rights marches, political campaigns and conventions, and the Watergate scandal that destroyed Nixon’s presidency.

But space travel was Rosenthal’s passion, and he was witness to more than 30 manned NASA flights, including the first moon walk and most of the Apollo missions. He also covered the Challenger shuttle tragedy, writing in the aftermath of the explosion: “Everybody said it had to happen sometime, but when it did, it was too terrible to believe.”

Covering a 1981 space shuttle landing, Rosenthal looked to the heavens to see Columbia “bursting like a silver wraith through mottled California skies.”

One of his greatest ambitions, never realized, was to be the first journalist to go into space.

“During the long, grinding days of manned space flight, Harry was like a campfire burning brightly — people gathered around him for warmth and light,” recalled Paul Recer, a retired AP science writer who covered space with Rosenthal. “He was generous with suggestions and wise counsel. We were all better journalists because Harry Rosenthal was there.”

AP Executive Editor Kathleen Carroll, who worked with Rosenthal in the 1990s, recalled being introduced to him when she joined the AP’s Washington bureau as a news editor. He remarked: “Don’t expect me to remember your name. My brain is already full up with names and I don’t have room for any more.”

He said the same about friends, she recalled, but that was “vintage Harry” and he didn’t mean it.

“I loved his stories, the ones he told and the ones he wrote,” she said.

Former AP Radio reporter Mark Knoller, now CBS News White House correspondent, witnessed Rosenthal’s ability to think on his feet when they were assigned to cover the public viewing of Elvis Presley’s body at Graceland in 1977, a cultural milestone of their careers. The Graceland staff placed the AP men at the head of the line, Knoller said, but “warned us, no photos and no lingering — that they would keep us moving quickly.

“So Harry suggested that we split our attention so we wouldn’t miss anything. He’d take the waist up and me the waist down.” Despite the precautions placed on everyone at the viewing, the National Enquirer published a photo of the singer in his casket.

Rosenthal’s coverage of Presley’s funeral was full of the small human moments that added up to a tale fit for Martha.

He wrote about the throngs filing through the cemetery a day after the funeral, many collecting flowers scattered by mourners:

“Among the thousands taking a flower were Paul MacLeod of Holly Springs, Miss., and his 4-year-old son Elvis Aron MacLeod.

“The father had grease-slicked hair, silver sunglasses, a white jacket, a black shirt and pointy-toed boots.

“Little Elvis, wearing a grin, clutched a carnation.

“‘Why, I even named my son after Elvis instead of naming him for myself,’ said MacLeod. “I’d like to be like Elvis in every way myself.”

“When he shouted to his son — ‘Hey, Elvis’ — it startled other pilgrims.”

Jon Wolman, who was Rosenthal’s boss in the 1990s as Washington AP bureau chief, called him “the quintessential general assignment reporter in journalism’s age of specialization,” one who could cover the courts one day, the White House the next and a feature with flair after that. “At every stop, he satisfied the readers’ curiosity with his enthusiasm and an eye for the telling detail. As a writer, he could dangle participles with the best of them.”

Rosenthal discovered newspapering as a young American serviceman in the Pacific at the end of World War II. In 1950, he began his career in daily journalism with a job at the Free Lance in Hollister, Calif. He left after a year to join AP’s San Francisco bureau, transferred to Kansas City, Mo., in 1952 and to the Washington bureau in 1967.

Rosenthal was born in Frankfurt, Germany, in 1927. At age 11 and traveling alone, he fled the Nazis.

Upon his arrival in the U.S., and before his parents followed him, Rosenthal wrote to his mother and asked that she stop calling him by his birth name, Heinz. Now that he was in America, he said, “I am Harry, not Heinz. Harry.”

He signed that letter, “Your son, Heinz.”

He became a U.S. citizen in 1945.

Rosenthal was a soldier awaiting the invasion of Japan when the U.S. dropped the atomic bombs that forced the Japanese to surrender. He was then assigned to the staff of the Pacific Stars and Stripes in Tokyo as a photographer and proofreader.

While in Tokyo, he became fluent in Japanese. He gained a working knowledge of Chinese when, after his retirement, he spent a year on the staff of a paper in Shanghai. And he never forgot his German.

“Once at a NASA news conference, a German scientist became thoroughly befuddled while attempting to explain something in English,” Recer said. “Harry saved the day by asking questions in German and then translating.”

Walter Mears, a retired AP vice president and former Washington bureau chief, said Rosenthal was “a great reporter, a gifted writer and an AP man to the core.”

Said Louis D. Boccardi, former AP president and CEO: “Harry was an original — a warm, wonderfully talented writer and reporter who loved his work, brought enthusiasm to every story he tackled and for decades graced our wires with elegant prose.”

During his long career at the AP, Rosenthal co-authored two books, “Triumph and Tragedy, The Story of the Kennedys” and “Calley.”

The month he turned 59, Rosenthal began writing a news column aimed at older Americans.

“Signs of aging don’t bother me,” he wrote. “Bifocals? I had them when I was 35. Baldness? My hair was in full flight at 40. The inability to play basketball like I used to? Well, I never did play basketball.”

Rosenthal’s notion of exercise was pushing chess pieces around a board and picking up a book.

He was a man of strong beliefs that, by today’s standards, would label him a liberal to many. To Rosenthal, a Jew who had experienced the reality of Hitler’s Germany, his opinions were expressions of the decency and compassion that made his adopted land a beacon of hope.

“I believe that not providing shelter for the homeless is an obscenity,” he wrote in his first column. “I believe there should be no one, of any age, who goes hungry or lacks medical care.”

His wife of 51 years, Naidene Rosenthal, died in October 2007, in Kansas City, Mo. She was a native of the city and the Rosenthals had moved back there several years after Rosenthal’s retirement.

He is survived by his daughter, a granddaughter, Megan, and a sister, Trude Plack. His son, David, also a journalist, died in 1991.