BERLIN (AP) — After months of overtime writing about upheaval and protests in East Germany , AP’s Frieder Reimold settled in on Nov. 9, 1989, to watch a televised evening briefing by Guenter Schabowski, a member of the Communist country’s Politburo.

History didn’t give Reimold a break that night. About an hour into the rambling news conference, Schabowski mentioned that East Germany was lifting restrictions on travel across its border into West Germany. Pressed on when the new regulations would take effect, he looked at his notes and stammered, “As far as I know, this enters into force … this is immediately, without delay.”

It was so offhanded that it took Reimold a little time to recognize the implications of the statement — that East Germany was opening the Berlin Wall and the heavily fortified border with West Germany. Carefully, Reimold, then the Berlin bureau chief of The Associated Press’ German service, typed out what has become his iconic alert: “DDR oeffnet Grenzen” — “East Germany opens borders.”

At first, nothing happened. In the days before the smartphone, news traveled more slowly. But less than one hour later, as West German broadcasters and West Berlin radio station RIAS began picking up the AP alert at the top of the hour in their news programs, East Berliners began jamming border crossings in Berlin. Border guards had received no orders to let anyone across, but within hours gave up trying to hold back the crowds.

“This was the alert that changed the course of the night,” Reimold says, looking back as Germany celebrates the 30-year-anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. “The alert sped up a development that sooner or later would have been inevitable in any case.”

Built in 1961, the Wall stood for 28 years at the front line of the Cold War between the Americans and the Soviets.

It had carved a 156.4-kilometer (97.2-mile) swath through Berlin’s heart and the surrounding countryside, and through the hearts of many of its people. Seeming as permanent as death, it cut off East Germans from the supposed ideological contamination of the West and stemmed the tide of people fleeing East Germany.

Despite the formidable obstacle and threat of stiff punishment, many tried to escape by tunneling under it, swimming past it, climbing or flying over it. At least 140 people died in the attempt, according to the latest academic research.

In the weeks leading up to Schabowski’s announcement the pressure had been building, with street protests in Leipzig, East Berlin and elsewhere. Thousands of East Germans had fled the country by seeking refuge in the West German embassy in Prague.

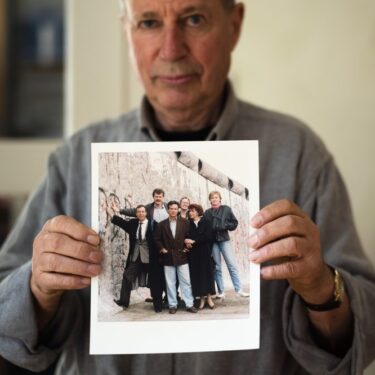

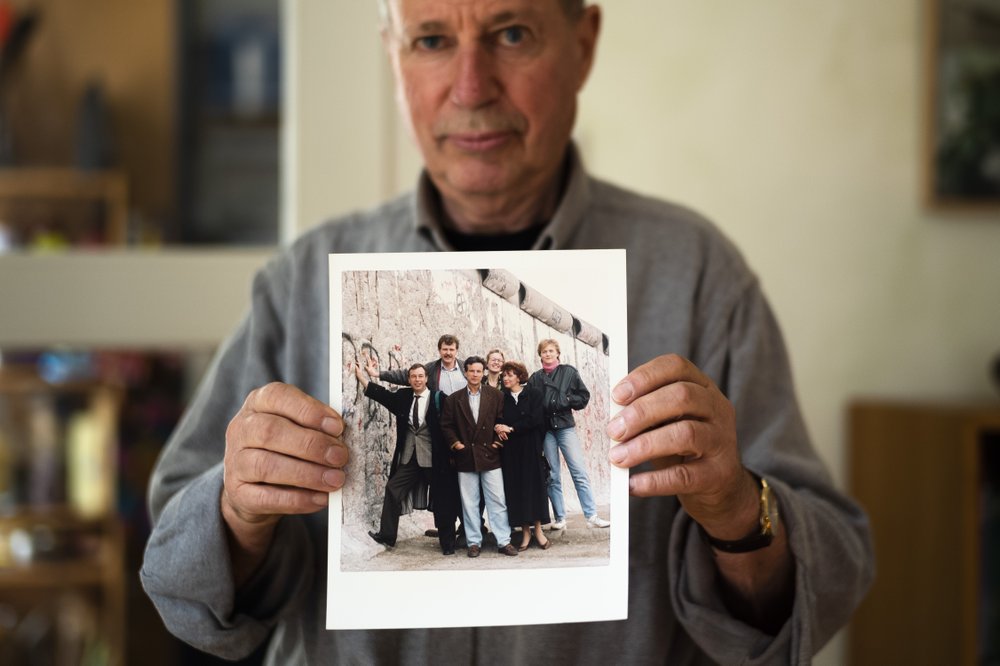

“As reporters and journalists, we had experienced everything up-close and under extreme pressure,” recalled Reimold, 75, who retired a decade ago. “We had cracked lips and red eyes from the exhaustion, we felt like we couldn’t go on any longer.”

Nobody had expected the border to be opened as quickly as it happened, however — and certainly not with such a humdrum announcement, which Reimold strained to listen to in the din of the AP’s West Berlin newsroom.

“One colleague was sitting next to the TV across the room from me and screaming over everything Schabowski had said, which was quite awkward,” Reimold remembered. “I had to simultaneously listen to him, listen to what Schabowski was saying on TV and at the same time write about it.”

Despite the confusion, Reimold sent out his alert at 7:05 p.m. Other wire services alerted the news as well, but none went so far that moment as to say that Schabowski’s announcement in fact meant that East Germany had opened its border.

Reimold’s AP alert is widely seen as having helped nudge the process along, and in a nod to its significance his words are today immortalized in a plaque in the sidewalk on Bornholmer Strasse, the border crossing where people first walked over from East to West.

That night, Reimold worked until 2 a.m. When he had finally sent out his last report, he got up and walked over to the office window overlooking the corner of Fasanenstrasse and Kurfuerstendamm — West Berlin’s most glamourous boulevard. Thousands of people from both parts of the city were streaming past the glitzy stores, drinking beer, celebrating freedom.

“And then along comes this little Trabi,” Reimold remembers, using the nickname for the typical East German Trabant cars. “It stops, scared, doesn’t know what to do with all the masses ahead.”

“Until somebody in the crowd notices what’s going on, pulls open the car’s doors, gets other people to join, and all of them bang their hands on the roof of the car and say: ‘Welcome, welcome, welcome to the West!’”

This was the moment, Reimold said, that he realized something in Germany had “definitively changed and was irreversible.”

“And that’s when I noticed that tears were running down my cheeks,” he said.

___

Randy Herschaft and Francesca Pitaro contributed reporting from New York.